Hope in Uncertain Times: a systems perspective

Lately, I’ve been thinking about dissipative structures—a concept from thermodynamics and systems science that explains how complex systems, from societies to ecosystems, evolve under stress. This ties into the Transition Design work I’ve been doing, which explores how we can intentionally guide long-term systemic change rather than merely reacting to current crises. This concept came up recently in a workshop with Fritjof Capra, who often weaves together physics, ecology, and systems theory, and was further illuminated in a related conversation with Terry Irwin, Professor in the School of Design and Director of the Transition Design Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, who introduced me to this intriguing framework.

Dissipative Structures – the core idea is that when systems are pushed far from equilibrium, they don’t necessarily collapse. Instead, they reach a bifurcation point—a moment where they either fragment or reorganize into something new, often something more resilient and complex. Sometimes, what emerges isn’t just a stronger version of what existed before, but something previously unimaginable—structures, ideas, and ways of being that wouldn’t have been possible under the old system.

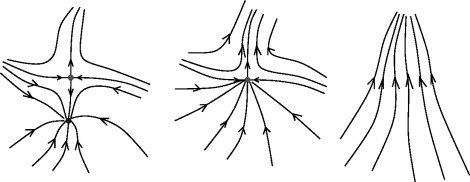

SCHEUERMANN & TRICOCHE in Visualization Handbook, 2005

This concept was deeply explored by Ilya Prigogine, the Nobel Prize-winning chemist whose work on dissipative structures revolutionized our understanding of how complex systems evolve. He demonstrated that instability doesn’t simply lead to disorder—it can also drive self-organization, allowing new forms to emerge from turbulence. His insights, which bridge physics, chemistry, mechanics, and social systems, help explain why moments of crisis—though disruptive—can also create openings for renewal. Fritjof Capra explores this in The Web of Life, illustrating how self-organization is a fundamental principle not just in nature but also in human institutions. In this sense, Transition Design aligns closely with Prigogine’s & Capra’s frameworks— it seeks to guide these far-from-equilibrium moments toward intentional, regenerative outcomes rather than leaving change to chance.

Looking at where we are right now—whether in politics, higher education, or global affairs—it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by uncertainty. And that uncertainty isn’t abstract. It means people losing jobs, rights being threatened, individuals and institutions struggling to adapt or even survive. Instability carries deep costs. But history also shows that moments of crisis, while devastating, can be turning points.

The End of the Bronze Age = The collapse of major civilizations, including the Mycenaeans, Hittites, and Egypt, led to a period of crisis. But in its wake, new societies emerged, including Classical Greece and the Phoenician trading networks that spread literacy and knowledge.

The Black Death = A catastrophe that killed millions, the plague upended feudal structures. Labor shortages forced economic shifts, giving workers more bargaining power and accelerating social change that helped set the stage for the Renaissance.

The Protestant Reformation = A movement born from religious dissent led to seismic political and cultural shifts. It fractured European society, causing wars and displacement, but also expanded literacy, redefined governance, and reshaped ideas of individual rights.

Europe’s Post-WWII Reconstruction = After the devastation of war, European nations made a choice: to rebuild not just their cities and economies, but their relationships. The Marshall Plan, the formation of the European Union, and diplomatic efforts turned former enemies into partners.

None of these transitions were easy or inevitable. They happened because people recognized the stakes, organized, and demanded something different. What might look like collapse is often a system at a breaking point—where change, while uncertain, becomes possible. But that possibility depends on action.

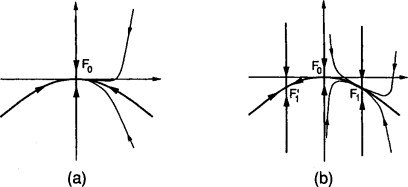

SCHEUERMANN & TRICOCHE in Visualization Handbook, 2005

Many instances of instability don’t result in renewal; they lead to further harm. But if we take a long-view perspective, we can see that instability often signals a need for transformation. It can reveal a door that was once locked—or even invisible—offering a path that wasn’t accessible before. Hope, in this sense, isn’t blind optimism—it’s the recognition that in critical moments of crisis, choices matter more than ever.

It’s about recognizing patterns of change, designing for long-term transformation, and actively shaping what comes next. The tension and polarization we feel today aren’t just signs of fracture; they indicate that old structures are being tested and that something is shifting. This kind of pressure can be destructive, but it can also be catalytic—forcing long-ignored issues to the surface, demanding engagement, and creating conditions for new directions to take root.

Paul Manneville, in Dissipative Structures and Weak Turbulence, 1990

The challenge is not just to endure but to take part in designing what follows. Healing and regrowth aren’t guaranteed, but they become possible when we recognize that in times of disruption, we have the greatest opportunity—and perhaps responsibility—to reimagine and rebuild. This doesn’t mean ignoring suffering or assuming that change naturally bends toward progress. It means engaging fully—not just resisting collapse but actively constructing something better. That work happens through forming new partnerships, reshaping systems, and making deliberate choices about the future we want to see.

Dissipative structures remind us that uncertainty isn’t just disorder; it’s also an opening. The question is, how will we step into it?